Christianity and Hinduism

By Swami Muktananda

For a Christian, practicing certain techniques from Hinduism can be compatible with their faith, provided these are reinterpreted and applied within the Christian framework, ensuring that Christ remains the central and sole path to salvation. This approach does not imply syncretism or an uncritical adoption of foreign doctrinal elements but rather the use of spiritual or physical tools that, stripped of their original religious context, can deepen prayer, strengthen the relationship with God, and enrich spiritual life.

The Catholic Church has explicitly recognized, in various documents, the presence of elements of truth and holiness in other religions. The Second Vatican Council, in the document Nostra Aetate (1965), affirms that “the Catholic Church rejects nothing of what is true and holy in these religions” (Nostra Aetate 2). This text highlights that traditions like Hinduism have profoundly explored fundamental questions about existence, the meaning of life, and the search for the divine, offering pathways that reflect aspects of universal truth. Within this framework, a Christian can integrate practices that promote values compatible with the Christian faith, such as contemplation, self-control, and inner peace.

Hinduism, in particular, offers a variety of techniques, such as meditation, breath control (prāṇāyāma), and certain forms of yoga, that do not inherently contain theological content contrary to Christianity. These practices can be reinterpreted as means to develop mindfulness, inner silence, and concentration on God. For example, a Christian might meditate using a Christian mantra, such as the name of Jesus, or contemplate biblical passages, integrating the technique into their spiritual tradition. This use does not seek to replace Christian prayer but to strengthen it by creating an environment of recollection and calm that facilitates communion with God.

The Catechism of the Catholic Church also refers to openness toward what is authentic in other religions, recognizing that the “seeds of the Word” are present in all cultures and spiritual traditions (CCC, 843). This teaching reinforces the idea that a Christian can adopt external practices as long as they are oriented toward a deeper relationship with Christ. For instance, breath control, used to quiet the mind, can be incorporated into the act of contemplative prayer without contradicting Christian principles.

Moreover, the Ad Gentes document of the Second Vatican Council encourages Christians to recognize the spiritual wealth of other traditions, stating that “whatever truth and grace are found among them, as a sort of secret presence of God, may enlighten men” (Ad Gentes 9). This acknowledgment allows elements of religions like Hinduism, when detached from their specific doctrinal meanings, to enrich Christian spirituality by providing tools to achieve serenity and depth in prayer.

It is essential, however, that any practice derived from Hinduism be reinterpreted in light of Christian faith and adapted to its theological context. A Christian who decides to adopt these techniques must do so while maintaining Christ as the center of their spiritual life, ensuring that these tools are used solely to strengthen communion with God. For example, yoga can be practiced as a physical exercise that promotes health and balance, without adhering to the philosophical or religious aspects that originally accompanied it.

The Church has also found historical precedents for the integration of contemplative practices from the East into Christian tradition. For instance, Jesuit missionary Matteo Ricci, during his mission in 16th-century China, used elements of Chinese spirituality to facilitate an understanding of Christianity among local scholars, demonstrating how cultural and spiritual techniques can serve as bridges for dialogue rather than threats to faith. More recently, Pope John Paul II, in his encyclical Redemptoris Missio (1990), emphasized that “the Church esteems everything that the Holy Spirit has brought about in the hearts of men and in the cultures of peoples, illuminating even non-Christian religions” (Redemptoris Missio 28).

From this perspective, techniques derived from Hinduism, such as mantra chanting, can be reinterpreted as forms of Christian praise. Instead of reciting foreign formulas, a Christian might chant traditional prayers, such as the Kyrie Eleison or the name of Jesus, using the technique to deepen their spiritual focus. Similarly, the physical postures of yoga, stripped of their original religious symbolism, can help prepare the body for prayer and foster an internal disposition of stillness and openness to God.

The document from the Pontifical Council for Interreligious Dialogue, Orationis Formas (1989), provides clear guidance on how Christians can use non-Christian methods of meditation. It underscores that these practices are acceptable as long as they do not distort Christian faith or endanger the centrality of Christ. This text highlights that meditation and contemplation are deeply rooted in Christian tradition and that external techniques are valuable only when subordinated to the search for the one true God revealed in Jesus Christ.

In conclusion, a Christian can practice certain techniques from Hinduism without compromising their faith, provided these are adapted and used as tools to deepen prayer and their relationship with God. The Church, in recognizing elements of truth in other religions, opens the possibility for these practices to be reinterpreted within a Christian framework, enriching spirituality without diluting the essence of faith. Thus, with proper discernment and Christ’s centrality as the foundation, these techniques can be integrated as means to progress on the path of sanctification, respecting the spiritual richness of both traditions.

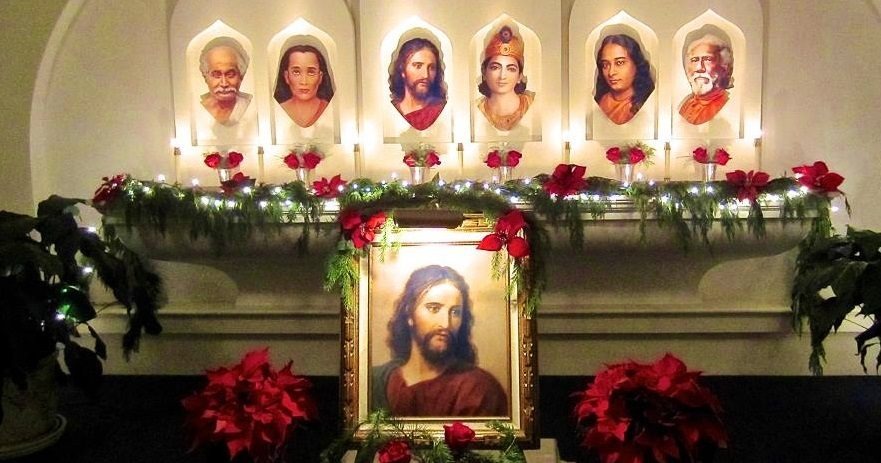

Ramakrishna Mission, Belur Math, India

Shivananda Ashram, Rishikesh, India

Ramakrishna Mission, Belur Math, India

Self Realization Fellowship, India

Ramakrishna Mission, Belur Math, India

Arunachala Ashram, Queens, NY, USA.