“Perfectionism, with its appearance of virtue and rhetoric of self-improvement, often functions as a device of concealment. Under the promise of excellence, it installs a logic of surveillance that, instead of stimulating development, only simulates it. Far from promoting authentic transformation, it imposes an idealized image that turns life into a permanent performance. Authenticity and sincerity, in this context, become a threat; spontaneity, a risk to be avoided. The individual does not grow, but adapts; does not advance, but disguises itself, moving around in a mask. In this dynamic, subjectivity is trapped in a regime of endless demands that, rather than liberating, restrains and imprisons. The metaphor of an invisible prison is particularly apt here: there are no bars, but there is constant pressure that regulates how we are in the world and with ourselves. Faced with this aesthetic and moral script of perfection, life resists. It does not respond to rules of symmetry or demand complete coherence. It behaves more like improvisation than a well-rehearsed performance. Living, in its most honest form, requires navigating the erratic, dealing with the unexpected, enduring even the ridiculous, laughing at ourselves. There is a peculiar dignity in accepted error, a form of knowledge that can only be attained when we abandon our obsession with success. Clumsiness, far from being a flaw to be corrected, is often the clearest language of our shared vulnerability. Removing it, eliminating it completely or pretending to do so, impoverishes the experience and distances it from its most fruitful condition: that of being a process in transformation.

Of course, this is not about idealizing or romanticizing imperfection or making mistakes an absolute value. Making mistakes is not a virtue in itself. However, when it becomes unthinkable or intolerable, error reveals something else: a fragility that is no longer cognitive, but existential. The need to appear flawless often masks a fear of being seen in our precariousness. It is therefore not surprising that those who cling most to the image of correctness are often those who fear most that they are not good enough. In such cases, perfection acts as a shield, not as an ethical horizon.

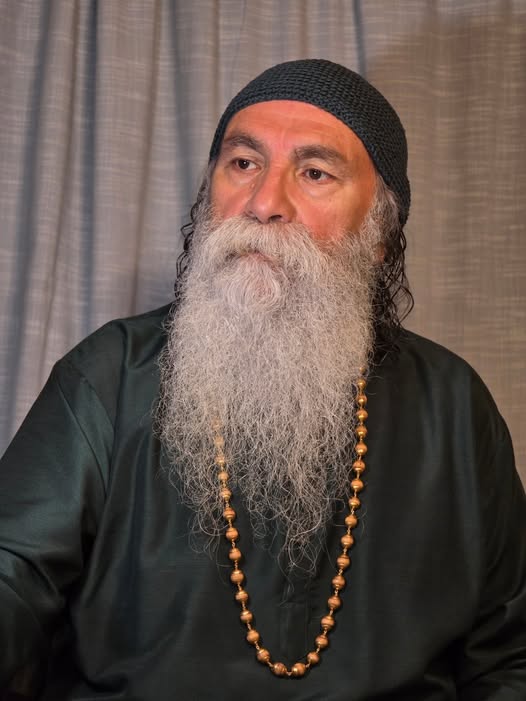

On a collective scale, this phenomenon takes even more complex forms. Public figures who embody unattainable standards—the impeccable religious leader, the uncontradicted thinker, the infallible professional—become normative models that render reality invisible. We are expected not so much to live as to function. Efficiency is privileged over life, the acceptable over the honest. The common, the ordinary, is displaced: fatigue, doubt, laziness, weakness, contradiction lose legitimacy. From there emerge, almost like inevitable reflexes, guilt—for not reaching the standard—and hypocrisy—to appear to have reached it. Between these two forces, the subject loses anchorage, torn between what they show and what they inhabit.

Regaining sanity does not, then, consist of adapting better to this order of expectations, but rather of allowing another relationship with oneself. There is a form of sensibility that is not measured by achievement, but by openness to reality. This zone, where it is no longer necessary to pretend, offers no epic deeds or spectacular rewards. Instead, it offers a form of unadorned presence, a being without the need for brilliance. There are no miracles there, nor any need to promise them. Only the possibility of inhabiting the world with your feet on the ground, without theater, without penance. In that difficult, often misunderstood simplicity, perhaps one of the most honest forms of freedom is at stake.”

Prabhuji