What is, as it is…

“Meditation does not consist of directing attention to a fixed point, nor of reaching a particular state of mind, nor of deliberately inducing some form of inner stillness. Nor is it an attempt to capture an essence supposedly hidden in the depths of the body. In its most rigorous sense, meditation does not involve searching, expecting, or producing an experience. Its most decisive act—and perhaps the most difficult to sustain—lies in suspending the belief that there is a subject who meditates.

The figure of the “meditator,” that subject who imagines himself traveling a path toward consciousness as if it were external, remote, or even inaccessible, is part of the same artifice that genuine meditation silently deactivates as it unfolds. There is no real displacement between the one who believes himself to be separate and that which he aspires to attain. Strictly speaking, there is no path to consciousness, for it cannot be located. It is not hidden behind the eyelids, nor does it take refuge in the pauses between breaths, nor does it slip through the cracks of thought. The Self—that name which different traditions have attributed to what has also been called Brahman, Consciousness, or simply That—does not present itself as a phenomenon or an event. It does not emerge in time or withdraw from it. It has no beginning and no end. It does not need to manifest itself in order to be. It is not contained in the body or specifically outside it, it is not channeled by any method, nor is it activated by the will. It does not depend on experience. It is, and its being is unconditional.

The idea that meditation is a means to attain consciousness contains a delicate conceptual error. It implies assuming that what has never ceased to be present must nevertheless be recovered. The logical structure of this assumption recalls the absurdity of imagining that the ocean must submerge itself in a drop in order to be recognized as water, or that space must contract into a corner in order to prove its infinity. Consciousness is not conquered. It does not begin. It does not occur… it does not happen… it remains.

Heidegger, in his later writings, articulates a related insight: “it does not matter what is given, but that it is given.” The essence of the phenomenon does not lie in the content of what appears, but in the very fact of appearing. This gift without origin or direction, without cause or purpose, is the mark of Being. The forms it takes—an image, a sound, a thought—have no ontological weight. The essential is not what is given, but the giving itself. What is given may vary; the fact that there is appearance is what cannot be reduced. Meditating, from this perspective, does not involve focusing on the contents of consciousness. It is not a practice of observing the breath, following the flow of the mind, or contemplating internal phenomena. Rather, it consists of clearly holding the evidence of what is happening without attribution or appropriation. Not from an exterior that controls or judges, but from the immediacy with which everything manifests itself as consciousness. Not within a framework that organizes the elements, but as a direct expression of what already is.

Even so, language becomes problematic. Every attempt to describe the unconditioned runs the risk of introducing a form that constrains it. Words, however refined, impose a boundary. And any attempt to define that which exceeds the concept, even with the utmost precision, incurs an inevitable loss. To name what cannot be named is to delimit it; to try to possess it is, in essence, to deny it.

Meditation, therefore, cannot be understood as a path leading to consciousness, because such a reading starts from an illusory separation. It is not a practice of the self aimed at obtaining what it still lacks, but rather the interruption of that fiction: the cessation of the self as the organizing instance of meaning. It is not a matter of acquiring anything, but of ceasing to hold that there is anything to be acquired. And when that abandonment occurs, discreetly, without calculation or pretension, no extraordinary experience ensues, nor is any dazzling truth revealed.

What remains is what is…

Unadorned… without interpretive framework… without decoration.

Simply what is, as it is…”

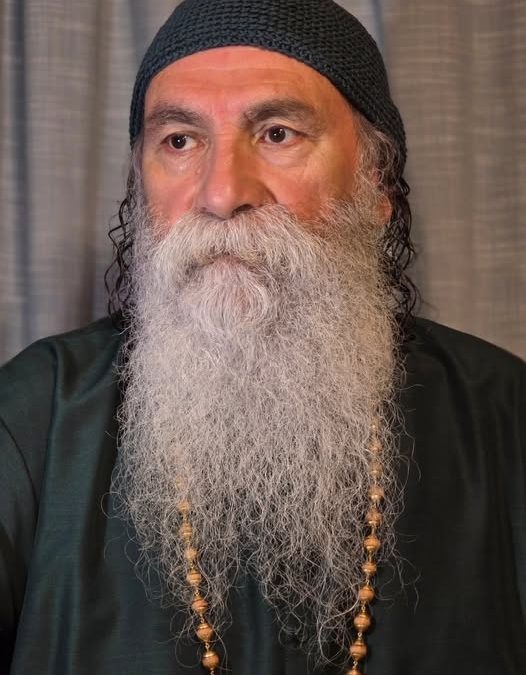

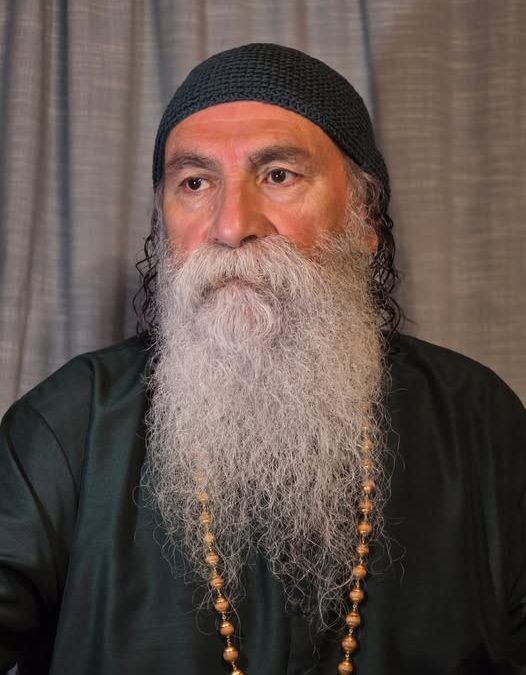

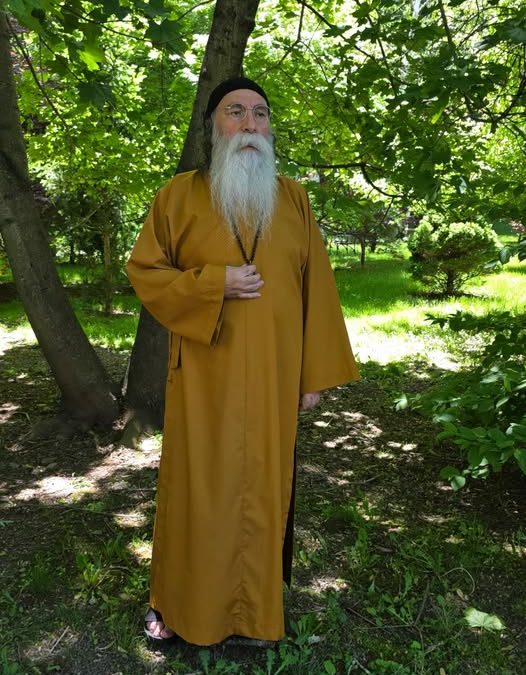

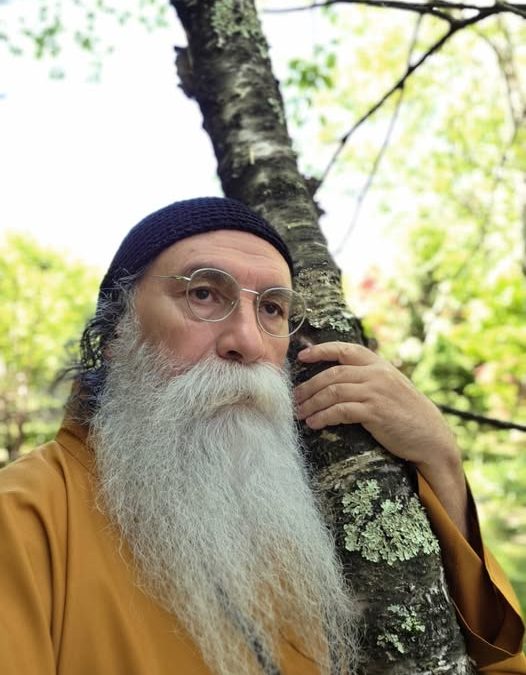

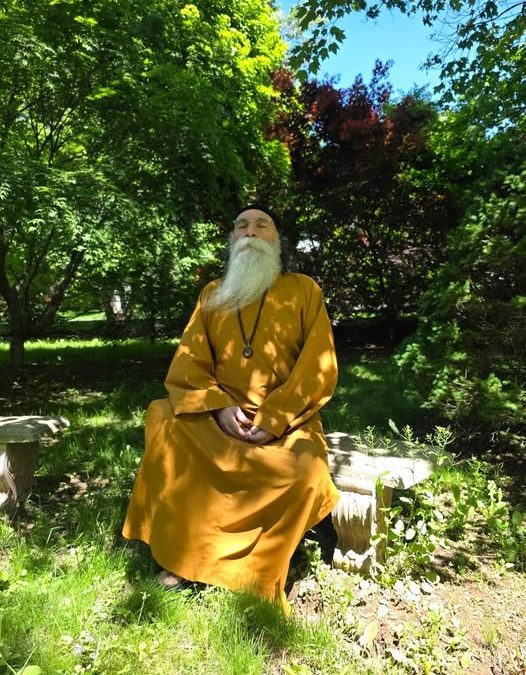

Prabhuji

Recent Comments