Integrating interiority and relationship

“In certain states of meditative contemplation, the impulse to withdraw from the world emerges. This movement does not express escape, but rather the need to confront one’s own consciousness without external interference. The inclination toward solitude is not a mistake. It is misleading to interpret it as a rejection of others or as a sign of opposition between connection and interiority. Radical autonomy has no basis. Subjectivity is always constituted in reference to others: we are born into a community, we share symbolic systems, and we participate in interpersonal emotional networks.

Martin Buber argues that the “I” is only constituted in the encounter with a “you.” The subject is not a closed monad, but a node of relationships that takes on meaning in reciprocity (cf. Ich und Du, 1923).

Internalization does not require the breaking of ties. Voluntary isolation is not a condition for self-knowledge. It is not necessary to exclude the other, but rather to silence the ego’s pretensions.

For Jean-Luc Marion, the subject is not a source of giving, but a receptacle for the gift that exceeds him. In the experience of love and contemplation, an ontological passivity of the self is revealed (Étant donné, 1997).

Those who reach a certain existential maturity understand that inner life and openness to others are not mutually exclusive spheres. Both can coexist without cancellation or fusion. Withdrawing from the world under the guise of introspection can become a form of evasion. Similarly, diluting oneself in exteriority without reflexivity leads to a loss of self. Integrating interiority and relationship requires the decentering of the self. Shared life is not opposed to authenticity. Joy does not come from isolation, but from the cessation of self-imposed identity demands.

Nishida Kitarō develops, from the Zen tradition, the notion of “the self as a place of negation,” where the self is not substance, but a function of a radical openness to the other and to nothingness (Zettai mujunteki jikodōitsu, 1932).

Serenity does not require constant reaffirmation of the self. It appears when the need to justify oneself to others or to maintain a defined image of oneself ceases.

It is not the world that must be abandoned, but the narcissistic representation of a self split from the whole. Once this fiction is overcome, reality unfolds as ontological communion.

In such a state, meditation and love are not mutually exclusive. By losing their compulsive nature, both practices reveal a structural unity that transcends all possessive or defensive logic of the self.

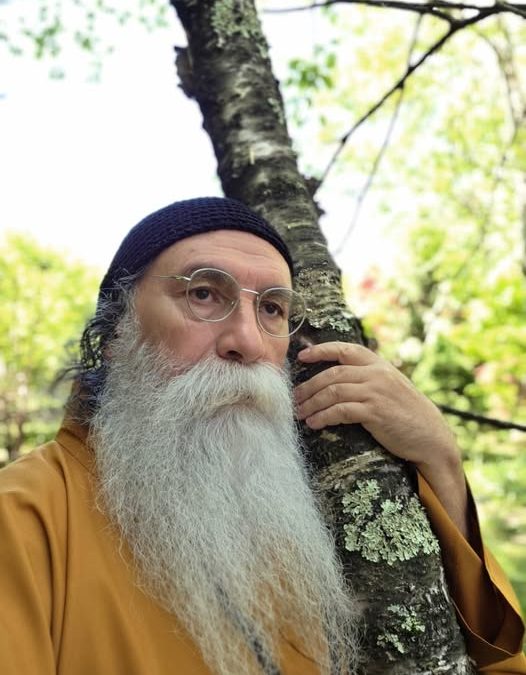

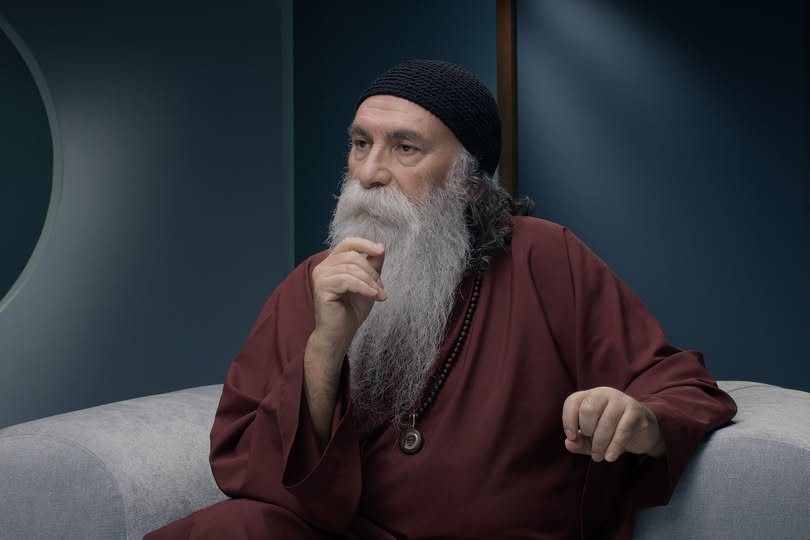

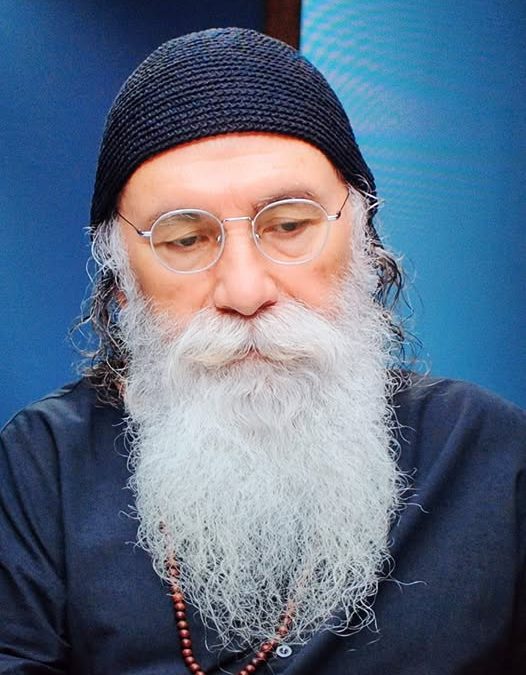

Prabhuji

Recent Comments